We must stop unjust deep sea resource grab

22.08.2023

Michael Lodge (ISA) and Gerard Barron (Metals Company) are sinking their teeth into the seabed.

Article by Guy Standing, Professorial Research Associate, SOAS University of London, and author of The Blue Commons: Rescuing the Economy of the Sea.

The world economy could be on the brink of lurching into a wild west frenzy of resource extraction and accelerated environmental decay. It concerns deep sea mining for what is undoubtedly a huge array of minerals, which mining advocates claim are needed for a greener technological revolution on land.

Under UNCLOS – the United Nations’ Convention of the Law of the Sea agreed in 1982, and since ratified by 167 countries and the European Union – mining in the deep sea (in the Area, which accounts for 54% of the world’s oceans) has been banned. The deal, explained in my recent book, was that it would be banned until there was an international agreement to protect the marine environment and an agreement on how the benefits would be share by all countries.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) was set up in 1994 to draw up the two agreements. After nearly 29 years, it has failed to do so. But there was a catch in UNCLOS. In an Appendix, it was stated that if a country party to UNCLOS collaborating with a mining corporation applied to start deep sea mining, the ISA had precisely two years to produce the agreements or applications to start mining could commence. In June 2021, Nauru and the Canadian TMC (The Metals Company) applied. So, in July 2023, without any agreement, applications could start.

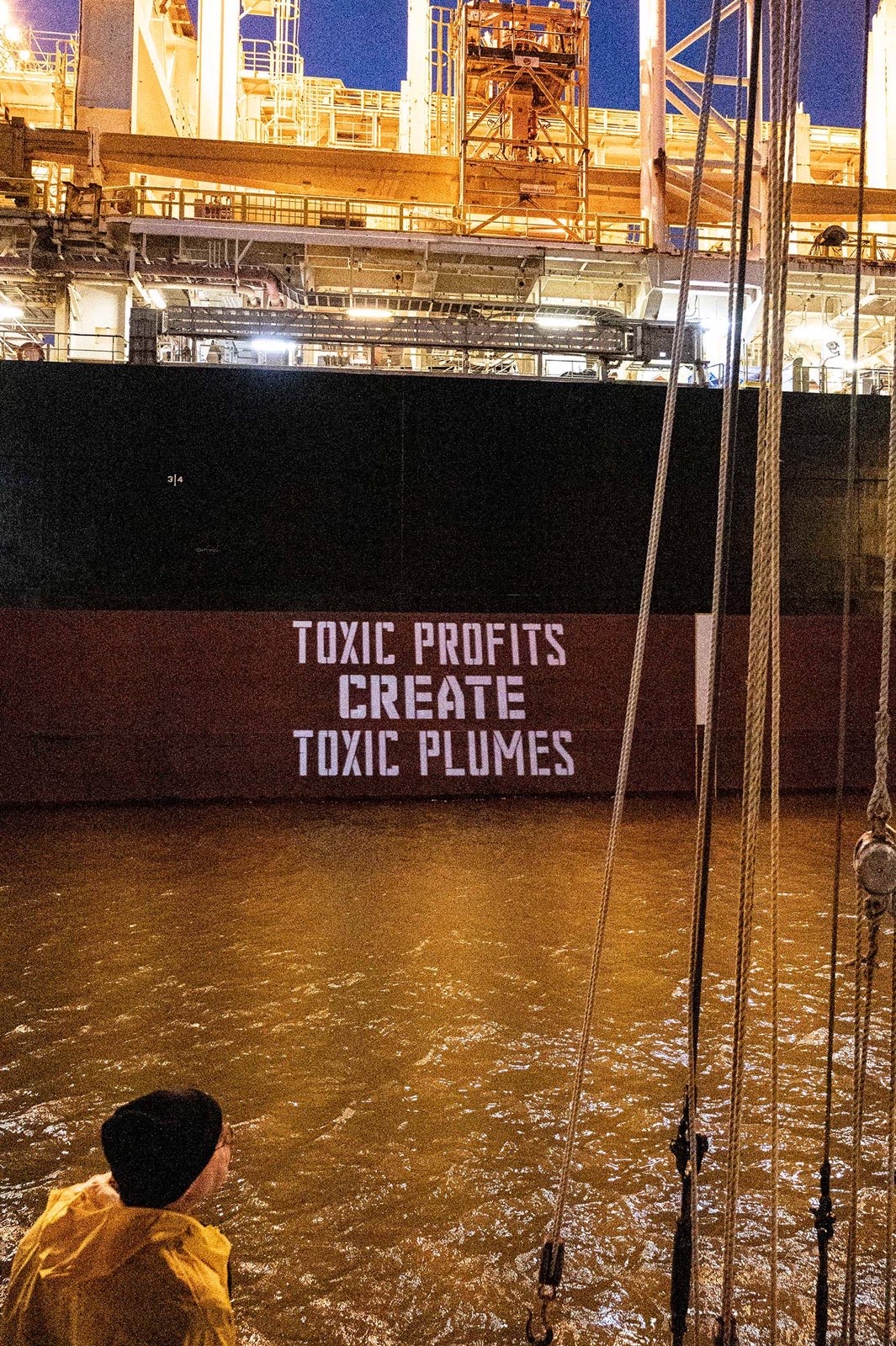

Ocean Rebellion illuminates the side of the deep sea mining vessel ‘Hidden Gem’.

Some alarmed governments, led by Spain, Germany, France, Ireland and Sweden, have demanded a moratorium – a ‘precautionary pause’ – all citing the potential ecological damage. In Britain, Labour has announced it would join the demand, for environmental reasons. They are right to do so. Hundreds of marine scientists have come out saying it would cause huge damage, including reducing the oceans’ capacity to act as a carbon sink.

However, a powerful pro-mining lobby is mobilising. Recently, The Economist has come out in favour. Its Leader on July 6 was headed ‘The world needs more battery metals. Time to mine the seabed’. It went on to minimise the ecological risks, asserting that the damage would be much less than mining on land, drawing on an article in its previous edition, which reads like a public relations puff from TMC, in which it was claimed that ‘mining the seabed is more environmentally friendly than mining in Indonesia’. The Leader said opposition reflected ‘questionable concerns of conservationists’, without mentioning that it is mainly marine scientists who are opposed to deep sea mining.

Those promoting it presume that such mining is necessary for a ‘green transition’, arguing that as there are insufficient minerals on land seabed mining is ‘inevitable’. Such reasoning neglects to consider that no such expansion may be necessary. Perhaps new technologies could reduce the need for such minerals, perhaps lifestyles could change to reduce demand for them. After all, less than 5% of lithium-ion batteries, used in electric vehicles, mobile phones and laptops, is recycled. And the main mineral needed for batteries, lithium, has not been found in the sea.

the main mineral for batteries has not been found in the sea

If deep sea mining takes off, one concern is that it will reduce the sea’s ability to act as a carbon sink, vital in combating global warming. Another is that recent German research has shown that the polymetallic black potato-sized nodules sitting on the seabed thousands of metres below the surface are highly radioactive. Bringing millions of tons of nodules up could harm human health. There is no evidence those developing a mining code have even considered this.

In the past month, as reported in the Financial Times and elsewhere, considerable attention has been paid to the environmental issues. But one aspect has been largely ignored in the media and by politicians calling for a moratorium. UNCLOS was initially motivated by several geopolitical concerns. Over 25 years of tortuous negotiations, what emerged was a complex set of compromises. The motivations were, first, a need to prevent great power conflict over the oceans’ resources and, second, to make sure that everything in the ocean was treated as ‘the common heritage of mankind’.

What emerged in 1982 was an agreement in which different groups of countries gained something and in return made concessions. What the advocates of deep sea mining now are saying, without acknowledging that, is that the rich countries should not honour the one major concession they made in return for major concessions made by developing countries, in particular. This would be profoundly unfair and regressive.

The ‘Polymetallic Nodules’ split ear drums outside the Deep Sea Mining Summit in Canary Wharf to highlight deep sea minings devastating noise pollution.

Briefly, all coastal countries acquired national ownership of 200 nautical miles from their shores, as Exclusive Economic Zones, amounting to a giant enclosure of 138 million square kilometres, with France gaining 11.4 million followed by the USA, Russia, Australia and the UK. The rich countries gained access to the fish populations of developing countries, which they have plundered unsustainably, and the great powers obtained freedom of navigation globally.

In return, the deep sea ‘Area’, covering 54% of the world’s oceans, was reserved as ‘the common heritage of mankind’. Developing countries, including 32 landlocked countries that are among the poorest in the world, agreed to UNCLOS solely on the basis of an assurance that if any resource extraction took place in the deep sea, the benefits would be shared on an equitable pro rata basis.

So, today’s advocates of deep sea mining are in effect saying the rich countries should jettison the one significant concession they made in return for all the gains they obtained. This is unethical and a 21st century neo-colonial resource grab, planning to take from the commons without compensation.

Ocean Rebellion illuminates the side of the deep sea mining vessel ‘Hidden Gem’.

The ISA was set up to produce not just a mining code that would respect the precautionary principle of doing minimal environmental damage but also a formula for equitable sharing. There is no such formula, and little prospect that one is being developed that respects the spirit or letter of international law.

As a result, there is a distinct risk that what could take place would amount to the biggest resource grab in history. And that could be overlaid by a new geopolitical power struggle, this time between China and a few other countries with mining ambitions. So far, 31 exploration licences have been issued by the ISA, with China having easily the largest number with five.

un isa licenses are creating the biggest resource grab in history

In this there is incredible irony. Back in 1982, although not formally a member, China led the G77 group of developing countries in demanding the benefits of mining should be shared across all countries. Today, while a large group of African countries has been lobbying for a 45% tax on all profits from taking minerals from the blue commons, China has led the opposition, demanding instead that there should be only a 2% tax and that the ISA should be encouraging ‘venture capital’ to put in money to accelerate corporate investment. The hypocrisy is breathtaking.

China has an impressive array of laws that seem to respect provisions of UNCLOS, as its minister in charge stated at the UNCLOS + 40 Conference in September 2022, and it claims to have ‘followed a sustainable approach to fisheries development’. Not only is this demonstrably untrue, but it is betraying the sharing commitment it led the charge to obtain.

Paradoxically, scared by the very real prospect that China will extend its control of global mining, the US Administration is expressing alarm at prospective Chinese domination. The alarm is justified, but the USA is partly to blame, since it is the one country that has resolutely refused to ratify the UN Convention.

The fate of the Ocean depends on us all.

Our interventions depend on your support.

There is no legal or moral ground for allowing a few multinational corporations to take and profit from the vast array of minerals under the sea. European countries must give this issue much higher priority than they have done so far. Norway has recently said it will start deep sea mining and a Norwegian company, Loke Marine Minerals, has even bought a British subsidiary of the US arms manufacturer Lockheed Martin that had acquired two exploration licences from the ISA in collaboration with the UK government. Europe thus stands divided.

Only a few European countries have called for a moratorium on deep sea mining, and even they have only emphasised the ecological concerns. They must not neglect the commons principles and the distributional imperatives. They are vital.

In response to an article in the Financial Times, the Chief Executive of The Metals Company says I ignore ‘the core tenet” of UNCLOS that mining should ‘ensure the participation of developing countries’, and he cites his company’s involvement of Nauru, Tonga and Kiribati. He thereby misrepresents my point, which is that the benefits of any such mining must be shared with all countries.

Photos by Savannah van den Rovaart (Hidden Gem) and Guy Reece (Canary Wharf), illustration by Ocean Rebellion.