So what are FADs (or dFADs)?

Large parts of the Ocean are like vast deserts, places where the sun shines relentlessly on the water and there is no shade. Occasionally, in these vast deserts, there is some floating debris. It might be a raft of dead plant life washed out to sea, a fallen palm tree or even a dead whale shark. This debris drifts on the currents of the Ocean and beneath it sea life thrives – attracted by the shade and the small marine animals that take refuge there. And these marine animals attract predators, first small fish, then tuna, and with the tuna arrive sharks and dolphins. Endangered whales and turtles also seek the shade while on migration. These little islands are an oasis in an ‘Ocean desert’. Little pools of thriving life.

But now a lot of these floating oases are traps. Traps set up by the neo-colonial EU industrial fishing fleet.

Fishing vessels rope together their own ‘floating debris’ using any plastic rubbish they can find like old fishing nets and buoys, pallets, plastic drums – anything that floats. And in this junk they place a satellite buoy. The whole lot is then dumped overboard to drift in the Ocean, which in itself breaks international marine pollution law.

The industrial fishing vessels don’t really wait – each vessel is in fact a massive tuna freezer and each vessel is deploying untold numbers of dFAD islands of debris in the Ocean every year. What they really do is constantly patrol the Ocean using the satellite tracking to visit the FADs they floated in the past – lurking until they’ve collected a community of marine life beneath them.

And when the FAD has collected a rich and diverse community of marine life a large net is dropped into the Ocean and carefully pulled deep under and around the FAD. The net is like a purse with a string (it’s called a purse seine net) and once it’s in place the top of the ‘purse’ is tightened by a crane so that everything beneath the FAD is caught in a massive bulging purse.

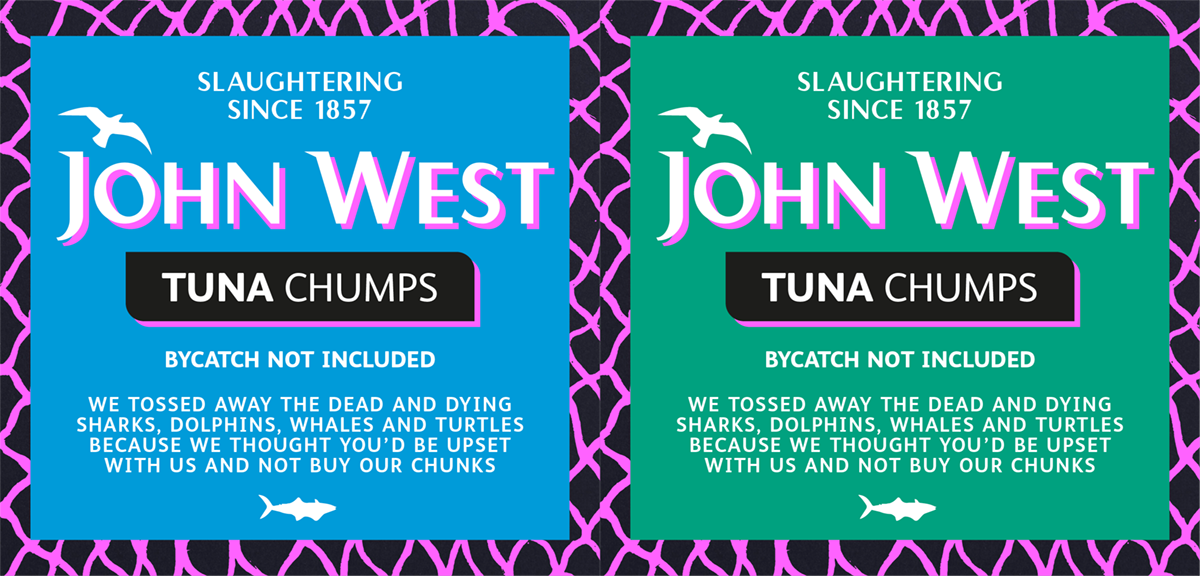

The ‘purse’ is hauled onboard and all its dead and dying catch emptied out for sorting. The fishing vessel is only interested in tuna but everything else is slaughtered too, the turtles, sharks, dolphins, everything. Of course this isn’t ‘on purpose’ so the fishing industry refers to the slaughter as ‘bycatch’ – a coincidentally caught (and killed) unfortunate byproduct of a lazy industrial fishing process.

The fate of the Ocean depends on us all.

Our interventions depend on your support.

Canned Tuna

John West sources their shark, turtle, and whale-killing canned tuna from Spanish fisheries in the Indian Ocean. This death-dealing tuna is sold by John West’s parent group Thai Union to supermarkets like TESCO, Iceland, Morrisons, Asda, Lidl and Aldi for their own-label tuna products, who then pass this wasteful and cruel product on to their innocent unknowing customers. These supermarkets excel themselves in their double standards, because they know that Thai Union has a dreadful track record. This Bangkok-based company owns a giant tuna cannery in the Seychelles that processes unsustainable drifting FAD-caught tuna from OPAGAC, the Spanish organisation of frozen tuna producers. In 2017, Thai Union promised publicly in a joint statement with Greenpeace that it would halve by 2020 its sourcing from industrial tuna fisheries that use harmful drifting FADs. Again, the world has waited seven years for Thai Union to deliver on their commitment to Greenpeace, but to date, no meaningful action has been taken by the company.

Going back further, according to The Guardian, in 2011 Princes and John West pledged to phase out the use of purse seine nets and fish aggregating devices.

Thirteen years later and the world is still waiting for this empty commitment to be fulfilled—in reality, Thai Union is just playing for time. Unfortunately, this type of unethical behaviour is typical in the world of tuna. Time after time, again and again, unscrupulous suppliers of unsustainable industrial tuna continue to break their promises, hoping that everyone will simply forget about them. Thai Union and Princes keep pledging to switch their sourcing to drifting FAD free purse seine fisheries, yet the plain fact of the matter is they never do. These kill companies benefit from the current status quo which is a chaotically dire lack of management and transparency in Indian Ocean fisheries. For fisheries in the Indian Ocean to be made truly sustainable, canned tuna producers must be mandated to independently develop the necessary tracking systems needed to not only ensure the full transparency and accountability of dFAD operations in their supply chains, but also to implement voluntary dFAD closures in those supply chains, instead of simply hiding behind government paralysis and inaction as an excuse for not taking meaningful action to protect the marine biodiversity that even those large corporate entities ironically benefit from.

Ocean Rebellion’s Bridget Turgoose says: “Time and again, Thai Union and John West have broken promises to cut down on these horrifically cruel drifting slaughterhouses. If you can’t trust them to keep promises, can you really trust the tuna they’re selling you? You’d really eat that? It turns your stomach.”

Ocean Rebellion’s Sophie Miller adds: “Trust the Spanish and French fishing fleets to indulge in this blatant over-exploitation of fisheries desperately needed by the hungry of poorer countries. Go West, John West.”

Tuna fish populations are crashing

According to scientists, yellowfin tuna populations in the Indian Ocean are crashing towards collapse. They are in the ‘red zone’, which means they are either ‘overfished’ or ‘subject to overfishing’. Whilst bigeye tuna was only declared as ‘overfished’ in 2022, yellowfin tuna has been in the red since 2015. The Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC) recently acknowledged that yellowfin tuna catches have in fact exceeded the “maximum sustainable yield” for well over a decade[1]. A recovery plan, complete with interim country-specific catch limits, has been in place for yellowfin tuna for almost as long as the stock has been overfished. The most recent stock assessment showed that a 30% reduction in catches (relative to 2020 levels) is now needed to allow the population to recover by 2030[2]. That translates into a catch limit of a little over 300,000 tonnes per year. In 2022, a staggering 413,680 tonnes of yellowfin tuna was caught[3] which is 37% higher than the recovery plan catch limit. Even skipjack tuna, the most abundant of the three, is being mismanaged in the Indian Ocean. A total catch limit has been in place since 2018 and, every single year since then, it has been systematically ignored. Last year’s over catch was the worst yet. Total catches should have been limited to 513,572 tonnes, but instead they reached an all-time high of 671,317 tonnes.

Why Tesco and why now?

Ocean Rebellion’s visit to TESCO was made to highlight its complicity in a harmful supply chain that includes John West, Thai Union and the MSC. The MSC’s dereliction of duty to offer consumers an “informed decision at their local retailer to buy fish products from a sustainable source” is particularly alarming. Ocean Rebellion would like to highlight this shocking carelessness to their funders, funders like the Bill and Lucile Packard Foundation and the Dutch Postcode Lottery, who will both be interested to find out that the MSC blue tick doesn’t mean ‘sustainably caught’ any more, instead it means nothing.

Ocean Rebellion demands that TESCO stop selling dFAD-caught tuna and John West / Thai Union also stop sourcing tuna from unsustainable European Union industrial tuna fisheries who use dFADs.

And, to all you innocent shoppers out there, now you know the facts, please don’t buy dFAD caught canned tuna or any tuna products from John West and Princes.

The fate of the Ocean depends on us all.

We’ll let you know what we’re doing to help.

Footnotes:

[1] Guillermo Gomez, Samantha Farquhar, Henry Bell, Eric Laschever & Stacy Hall (2020). ‘The IUU Nature of FADs: Implications for Tuna Management and Markets’

[2] Banks, R., and Zaharia M. (2020)‘Characterization of the Costs and Benefits Related to Lost and/or Abandoned Fish Aggregating Devices in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean

[3] Quentin Hanich, Ruth Davis, Glen Holmes, Elizabeth-Rose Amidjogbe and Brooke Campbell (2019). ‘Drifting Fish Aggregating Devices (FADs) Deploying, Soaking and Setting – When Is a FAD ‘Fishing’?